What Makes Urban Areas Tend to Vote Blue?

Part Three of Blue City Warrior Visits Red America: In Search of Us

This is the third part of my series Blue City Warrior Visits Red America: In Search of Us. Go HERE to read the Blue City Warrior opening essay. Please subscribe to follow my journey!

Learning from my own life experience, I have assumptions about why city dwellers are more likely to vote blue. For me, living in core cities for most of my life, put me in proximity to people that were different from me. It gave me an appreciation for all the other ways of being in the world, an empathy for those that have less than I do, and a trust in our ability to govern ourselves through democratic processes.

But, hey! It’s not just me! This understanding is corroborated by academic research and other political commentators. And it’s leading to the big divide we have in our current national politics.

The late American political scientist Ronald Ingelhart argued that when people are economically and physically secure they have a better ability to shift their attention from being worried about outsiders and the need to pull your community closer to being more open to new ideas and tolerant of outsiders. Called Modernization Theory, this trend towards openness to others ascended in the latter half of the 20th Century in industrialized, urbanized areas, and helped result in shifts in attitudes on gender equality, religion, and democratic values more common in liberal democracies in the United States and Western Europe.

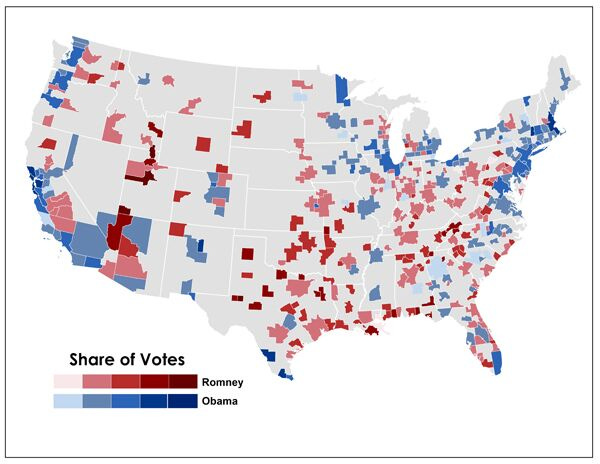

Ingelhart’s theory can also help explain why it is also true that while yes, some cities are blue, there are also cities that are not. As Richard Florida wrote in the aftermath of the 2012 Presidential election in which Democrat Barack Obama won 11 of the 15 largest American cities over Republican Mitt Romney, “not all urban areas are bastions of blue. Population, density and education all play a role.”

What Florida found was that the cities that voted for Obama in high numbers tended to be more dense. The average Obama metro was more than twice as dense as the average Romney metro. Investigative journalist Dave Troy even calculated the inflection point as roughly 800 people per square mile. Below 800 people per square mile, there was a 66 percent chance that someone voted Republican. Above 800 people per square mile, there was a 66 percent chance that someone voted Democrat.

Education also played a role. Metro areas with a higher number of college graduates – especially those that work in what Florida calls the “creative classes…science and technology; business and management; healthcare; education; and arts, culture and entertainment” – voted for Obama. Alternatively, working class metros with a lower percentage of college educated voters, voted for Romney. Despite all of Obama’s union endorsements, and the narrative on the right that Obama bought votes by offering “welfare, food stamps and other entitlements,” Florida found “no statistically significant association between Obama votes and the metro poverty rate, and only a very small one for income inequality across metros.”

In the end, Florida determined in 2012 that economic forces were driving the divide, where more affluent, high-skilled cities were more likely to vote blue, whereas less advantaged, less skilled cities were increasingly voting red.

Of course this trend has only grown since then. As Florida reported in a review of the 2016 election, the Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton won the largest metro areas at percentages greater than Obama did in 2012, whereas Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump outperformed Romney in economically damaged rust belt cities and rural areas.

Increasingly, economically successful urban areas are voting blue, where those urban areas that are not are voting red. In 2016, the 472 counties that went for Clinton generated 64 percent of the nation’s aggregate economy, whereas the 2,584 counties that Trump won were responsible for just 36 percent.

By 2020, the blue versus red voting divide between the most heavily populated areas with high economic activity and the least populated counties with less economic activity, continued. According to the Hill and Brookings, Democratic nominee Joe Biden won 91 of America’s 100 counties where the largest cities and urbanized metro areas are located, which represented over 70 percent of the country’s economic activity. In contrast, Republican candidate Donald Trump carried 95 of the 100 counties with the smallest populations, encompassing just 29 percent of the economy.

A study in the Journal of Rural Studies summarized it this way: “In 2020, Trump's margin of victory in rural areas was even greater [than in 2016]. Trump’s 2020 election loss was a consequence of higher voter turnout in urban areas [with] Trump's greatest support [coming] from white, working-class counties.”

Aligning with Ingelhart’s Modernization Theory, residents of prosperous urban areas are more economically and physically secure, leading them to be more tolerant of others, open to diverse ideas, and value democratic decision-making – further leading them to be more likely to vote blue. Alternatively, the people and communities who instead feel economically and physically at threat, are closing ranks around their communities, warning of unknown “outsiders”, and have less trust in the government's ability to provide the things they need – leading them to vote Republican in higher numbers.

But, yet, there are still urban areas where people engage in robust economic activities, live in proximity to others, and elect Republicans up and down their ballot. It’s not just that there are Republicans who live in cities, but there are cities that are as red as my city is Blue.

Which got me wondering, what are those places like?

As much as I like my blue city with its high walk score, numerous Little Free Libraries, and Black Lives Matter signs, I recognize how destructive the trend towards segregated political spaces is to our country and our country’s democracy. I’ve also become increasingly interested in getting out of my blue bubble and seeing what it’s like on the other side. Instead of going to a coffee shop where I can assume the others share much of the same political outlook as I do, I want to venture into a place where I can be exposed to a bit of difference. At least politically.

This election year feels like the right time for this venture. Instead of traveling to my favorite blue places, I’m going to spend my travel budget to venture into red places, and approach them with the same sense of curiosity that I approach any place I visit. How did this place come to be? Why was it started here, and how did it develop? How did race, economic cycles, and transportation infrastructure impact the way it grew? What are the must see public spaces? Local food? Brewery?

And also, maybe I’ll get a chance to meet some locals and find out what they like about their city. Do they like the same things about city living that I do? What do they like about their neighborhood, their neighbors? What are their concerns about their future, their families, their children? And if they like similar things as my (Democratic) peeps and me, and have similar concerns about our futures, is that just a small place to start bridging the divide?

Subscribe to follow my journey!