Tulsa, Oklahoma, Part Two: Racism’s Impact on the Geography of Tulsa

Part Seven of Blue City Warrior Visits Red America: In Search of Us

This is the seventh part of my series Blue City Warrior Visits Red America: In Search of Us. Go HERE to read the Blue City Warrior opening essay. Please subscribe to follow my journey!

I headed to Tulsa, Oklahoma as part of my travels in part because of its legacy as the hometown of the worst incident of racial violence in the United States, the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. I wanted to see for myself what the Greenwood neighborhood that was destroyed in early summer, 1921 looked like today. And I wanted to witness how the city and its current residents pay homage to the tragedy. With my interest in urban planning and the history of American cities, Tulsa is a fascinating case study. What does it look like today, and what are the forces that impacted it? How are the scars of 1921 reflected in the streets and neighborhoods of Tulsa in 2024? And as a Blue City Warrior from a progressive northern city, how might Tulsa’s experience differ from Minneapolis’, a city of similar size, but very different beginnings.

I also want to say right up top that I was just a short-term visitor to Tulsa and am by no means an expert on the race massacre and its aftermath. I am grateful to all the chroniclers who’s work I’ve studied on my way to understanding enough of the basics to not embarrass myself too much. I’ve linked to a few resources in case you want to explore the topic further yourself.

The Event

The racial violence began during Memorial Day weekend 1921 after Dick Rowland, a black shoe shiner, was accused of assaulting Sarah Page, a white 17-year-old elevator operator, in a downtown office building. On the evening of May 31, a group of white men, fueled by a local paper’s incendiary coverage of the accusation, invaded Greenwood. By noon on June 1, the Oklahoma National Guard imposed martial law, ending the massacre. Over just 24 hours, the white mob destroyed the robust Black district, burning 35 city blocks that included 191 businesses, 1,256 homes, schools, churches, and the Black neighborhood’s only hospital. Estimates are that as many as 300 people were killed, some shot, many burned to death, with estimated property losses of $3,500,000. (You can read more about the events of May 30 - June 1, 1921 here and here.)

The Aftermath

Greenwood business owners and residents faced complete devastation of their homes, lives, and community. They also faced hostility from the white institutions as they began the work of rebuilding. The white resistance to the rebuilding of Greenwood was so immediate that some observers think there was a plot to destroy the successful Black community even before Rowland and Page met in the downtown elevator.

Within days after the violence, a local newspaper published an editorial titled “It Must Not Be Again”, which stated: “the old ‘N*****town’ must never be allowed in Tulsa again.” Acting as the Tulsa Real Estate Exchange, a group of Tulsa’s Klan-connected businessmen immediately began a campaign to purchase much of the Greenwood land to turn it into an industrial and wholesale district adjacent to downtown. They urged the city to move the burned out Greenwood survivors further north out of the downtown area. They were aided by the Tulsa City Commission, which proposed new zoning and building codes that would both change the zoning of the area from residential to industrial and to also require any new construction in Greenwood be made of fireproof materials and be at least two stories tall. These new requirements would have made replacing the destroyed properties much more costly. (In the end, the new ordinance was challenged in court by Black Greenwood attorney B.C. Franklin, which ultimately led to it being struck down by the Oklahoma Supreme Court as unconstitutional, thus allowing Greenwood property owners to begin rebuilding in earnest.)

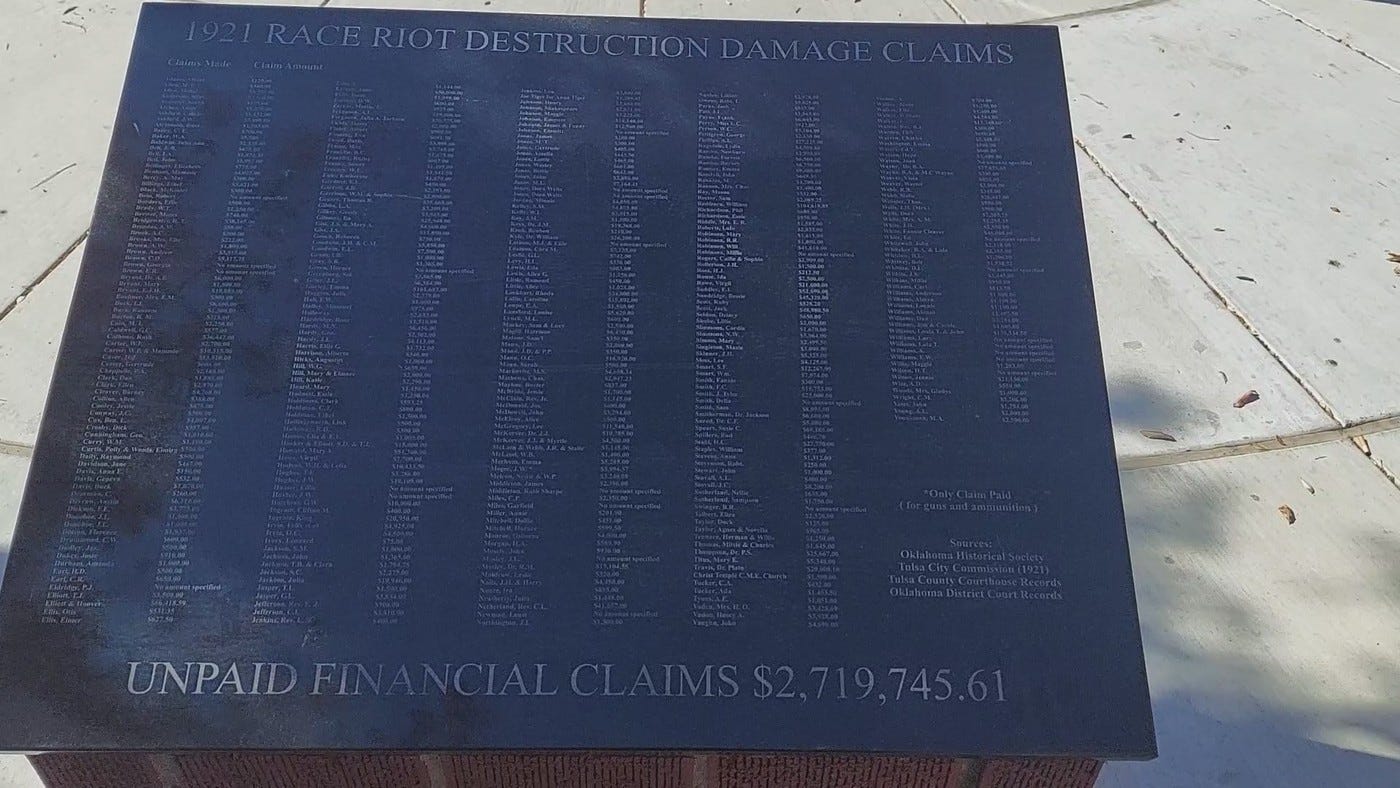

Insurance companies also created barriers to reconstruction by systematically denying every insurance claim based on “riot exclusion” clauses in policies. Claimants argued that the violence was not a “riot” as the Mayor and Police Chief called it, but rather was caused by city law enforcement’s response. Specifically, Black insurance policy holders pointed to the police department’s deputizing white men from the mob to act on behalf of the under-prepared police department. Many of the hastily deputized “officers” were later seen engaging in the evening’s violence. The Greenwood Cultural Center calculates the unpaid insurance claims at $2,719,745.61 in 1921 dollars. In the beginning, there were a few white voices calling for the city and state to financially support rebuilding efforts, but in the end, rebuilding and its costs were left to the victims of the violence.

Some community members fled Tulsa for good after the violence, depriving the area of important leaders. Some felt that Tulsa was no longer a safe place for their families and went to seek economic stability in other towns that may be more welcoming. Others, including the two original Black settlers of Greenwood and leaders in the creation of its vibrant business district, O.W. Gurley and J.B. Stradford left after losing their fortunes in the destruction. Stratford was also one of the nearly ninety Black men that were indicted by the Oklahoma State Attorney General’s grand jury who investigated the causes of the violence. Tulsa Star editor A.J. Smitherman was also arrested for “rioting” because he helped organize Black men to defend Rowland and the residents of Greenwood.

(A great resource on the story of the obstacles of rebuilding is the Human Rights Watch’s report on The Case for Reparations in Tulsa, Oklahoma, published in May 2020.)

The Renaissance

While there were many hurdles to rebuilding, Greenwood residents found ways around the barriers and persevered to rebuild their homes, businesses, and cultural institutions. By December 1921, the American Red Cross, who had come in to support the community in the aftermath of the violence, reported that over 700 buildings had been rebuilt. By 1925, Tulsa’s Black community was once again known as a center of economic success, with several historians arguing that the 1920s was when Greenwood really became Black Wall Street. By 1942, there were 242 Black-owned businesses operating in Greenwood – more than existed in 1921.

One of the factors that made rebuilding possible was that so many people owned their own property. Owning the land under the rubble gave property owners the ability to secure mortgages from financial institutions, and even build community lending pools, the Wall Street Journal reported. This was critical in seeding a local economy of Black-owned businesses for the next decades – especially after being shut out of resources by the city, state, and insurance companies. This also played a role in Black Tulsa bucking the trend in homeownership rates. By 1940 the Black homeownership rate in Tulsa was 49 percent, outstripping that of white residents, at 45 percent.

Of course, part of this concentrated economic success was out of necessity. Jim Crow laws were adopted in Oklahoma almost immediately after statehood was granted in 1907. In Jim Crow Tulsa, Black Tulsans were limited to where they could live, go to school, shop. One of Tulsa’s early zoning regulations was the 1916 housing ordinance that prohibited Blacks from living in neighborhoods that were at least 75% white – and vice versa. Even after race-based zoning was declared unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court in 1917, racial segregation in housing was institutionalized through racially restrictive covenants. (Racial covenants are clauses that were inserted into property deeds to prevent people who were not white from buying or occupying a home or land. Learn more about racial covenants here. Learn more about the history of race-based zoning in American cities here.)

These laws that limited where people could buy property and live based on the color of their skin created racially segregated cities across the country, not just Tulsa. They also created Black hubs of commerce where Black-owned retail stores, entertainment venues, services, educational facilities were built to serve the needs of the Black community. Much of it existed outside of the view of white residents, as a form of resistance and survival by Black Americans.

As Nonprofit Quarterly reports it, Greenwood experienced a renaissance in this post-massacre time of racial segregation. In the 1940s and 1950s, “grocery stores lined the commercial spine of North Greenwood Avenue, and the district featured chili parlors, movie theaters, barbecue restaurants, drugstores, pool halls, and doctors’ offices.” A local business directory published shortly after the end of World War II by the Greenwood Chamber of Commerce rejoiced that “Today after some 25 years of steady growth and development, Greenwood is something more than an avenue—it is an institution.”

But even in this era of relative stability for the Greenwood District, new federal programs were planting the seeds that sowed the conditions for what some call the “Second Destruction” of Black Wall Street.

The Second Destruction

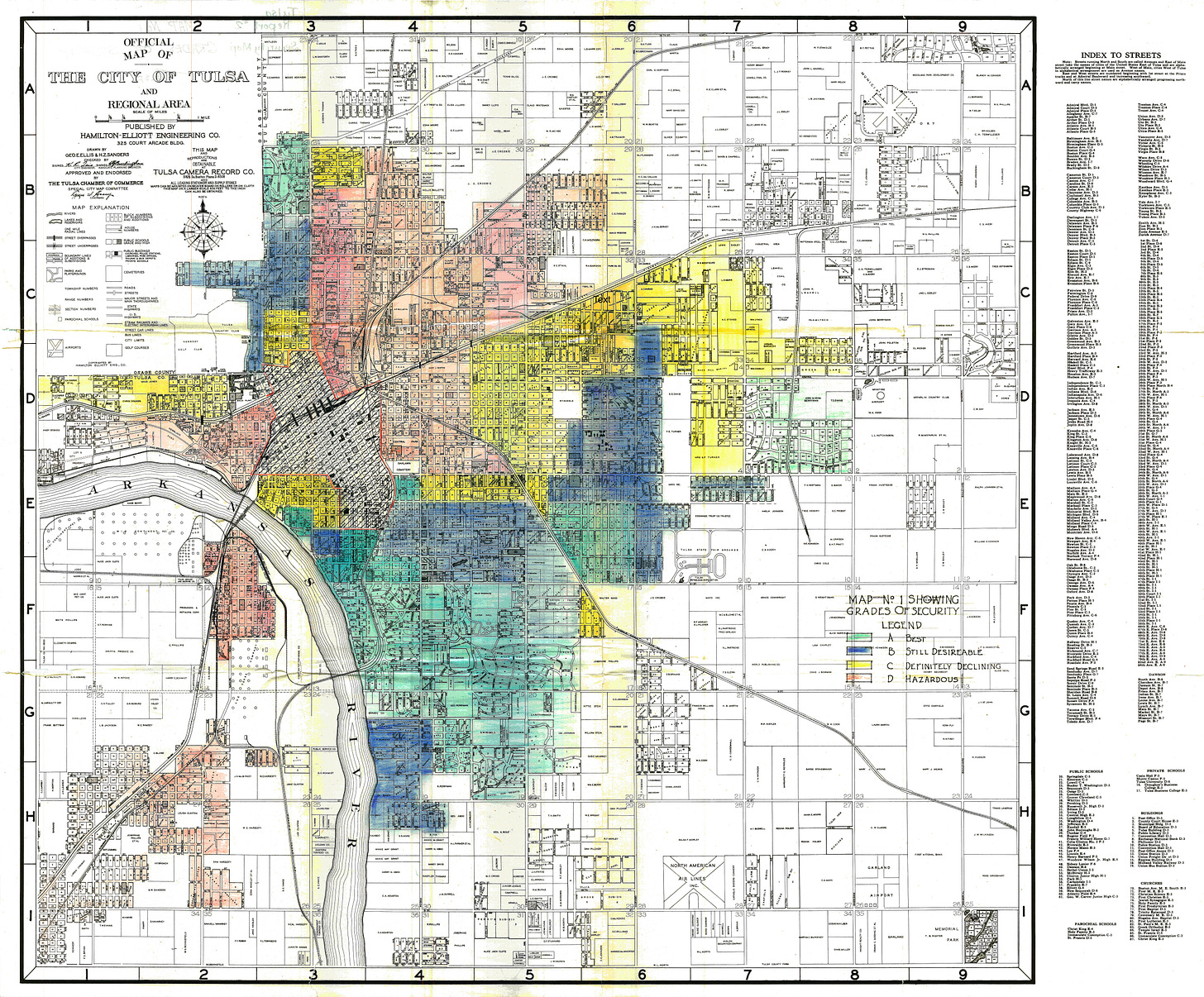

As part of the New Deal programs put in place to help Americans find economic stability in the wake of the Great Depression, the federal government established the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) to help people build wealth through homeownership. To help mortgage lenders determine if a real estate loan was a safe investment, HOLC created color-coded maps for 239 cities, including Tulsa. Neighborhoods were graded with one of four categories from green (“the best”) to red (“hazardous”). “Redlined” areas, composed of mostly low-income people of color, were deemed to be credit risks, making it nearly impossible for many residents to access mortgage loans from area banks. Needless to say, most of the historic Greenwood District was coded red, as were Black communities in cities across the country.

While homeownership rates increased across the country, it was white families that benefited from government-backed loans to purchase homes in non-redlined neighborhoods. In Greenwood – a redlined Black neighborhood – these policies had the effect of stunting economic investment in the entire neighborhood. Homeownership rates between Blacks and whites that were fairly equal in 1940 began to diverge. And the lack of access to financial resources by area property owners, led to properties looking increasingly run down. After several decades, this disparity in investment made Greenwood a top target when urban renewal and federal highway funding came to town.

(“Redlining” now means a lot more than banking practices based on the historic HOLC maps. The practice of discrimination in housing was made illegal in 1968 with the passage of the Fair Housing Act, but many of the discriminatory real estate lending practices remain. A 2018 analysis of publicly available data under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act found that Black Tulsans were 2.4 times more likely to be denied home mortgage applications than white applicants in Tulsa, and the 2020 Census shows a 30.6 percent gap between the white (69.3) and Black (38.7) homeownership rates in that city.)

The economic forces that helped fuel the establishment of Black Wall Street in Tulsa’s early years and its resurrection after the race massacre were no longer there in the years of redlining and financial disinvestment. The pieces of community wealth and resilience that were there may have been strong enough to hold Greenwood through the impact of federal policies that negatively affected the growth of other Black neighborhoods throughout the country, but that famous Greenwood resilience couldn’t withstand urban renewal and the arrival of the highway system.

As early as 1957, Tulsa’s Comprehensive Plan included creating a new tangle of highways encircling the downtown area. Like an arrow, one went right through historic Black Wall Street. In the name of combating blight, the city used condemnation and eminent domain to demolish over 1,000 properties mostly in Greenwood to build the I-244 highway. People were forced to move, and businesses were forced to close or relocate far away from their customers. As Carlos Moreno reported,

“An article in the May 4, 1967, issue of the Tulsa Tribune announced, “The Crosstown Expressway slices across the 100 block of North Greenwood Avenue, across those very buildings that Edwin Lawrence Goodwin, Sr. (publisher of the Oklahoma Eagle) describes as ‘once a Mecca for the Negro businessman—a showplace.’ There still will be a Greenwood Avenue, but it will be a lonely, forgotten lane ducking under the shadows of a big overpass.”

“Mabel Little, whose family lost their home and businesses in the 1921 massacre,” Moreno continued, “rebuilt and lost them both again in 1970. Little told the Tulsa Tribune in 1970, ‘You destroyed everything we had. I was here in it, and the people are suffering more now than they did then.’”

Even without the race massacre of 1921, Tulsa’s Black community was in for inevitable destruction as a result of federal policies that negatively impacted Black communities throughout the United States. Whatever resilience Tulsa’s Black community held because of its economic benefits at Greenwood’s beginnings were systematically paved over with the highway construction.

The Tulsa Urban Renewal Authority didn’t just take properties needed for highway construction. Other property targeted include blocks and blocks of housing to build the site where Oklahoma State University (OSU-Tulsa) now sits. Before the massacre, it was where Booker T. Washington High School, Greenwood’s main high school was located. Note the number of surface parking lots.

Minneapolis

Exploring Greenwood’s attempts to thrive in the face of white violence and anti-Black housing policies causes me to reflect on Minneapolis’ experience with those same forces. As much as we Minneapolitans like to think of ourselves as a liberal haven – after all we are the home of civil rights champions Hubert H. Humphrey (see 1948 Democratic Convention speech) and Walter Mondale (see 1968 Fair Housing Act) – racially restrictive covenants, redlining, racial violence, urban renewal, and highway construction have all shaped how my city remains at the top of lists of places with the largest Black v white homeownership and wealth gaps.

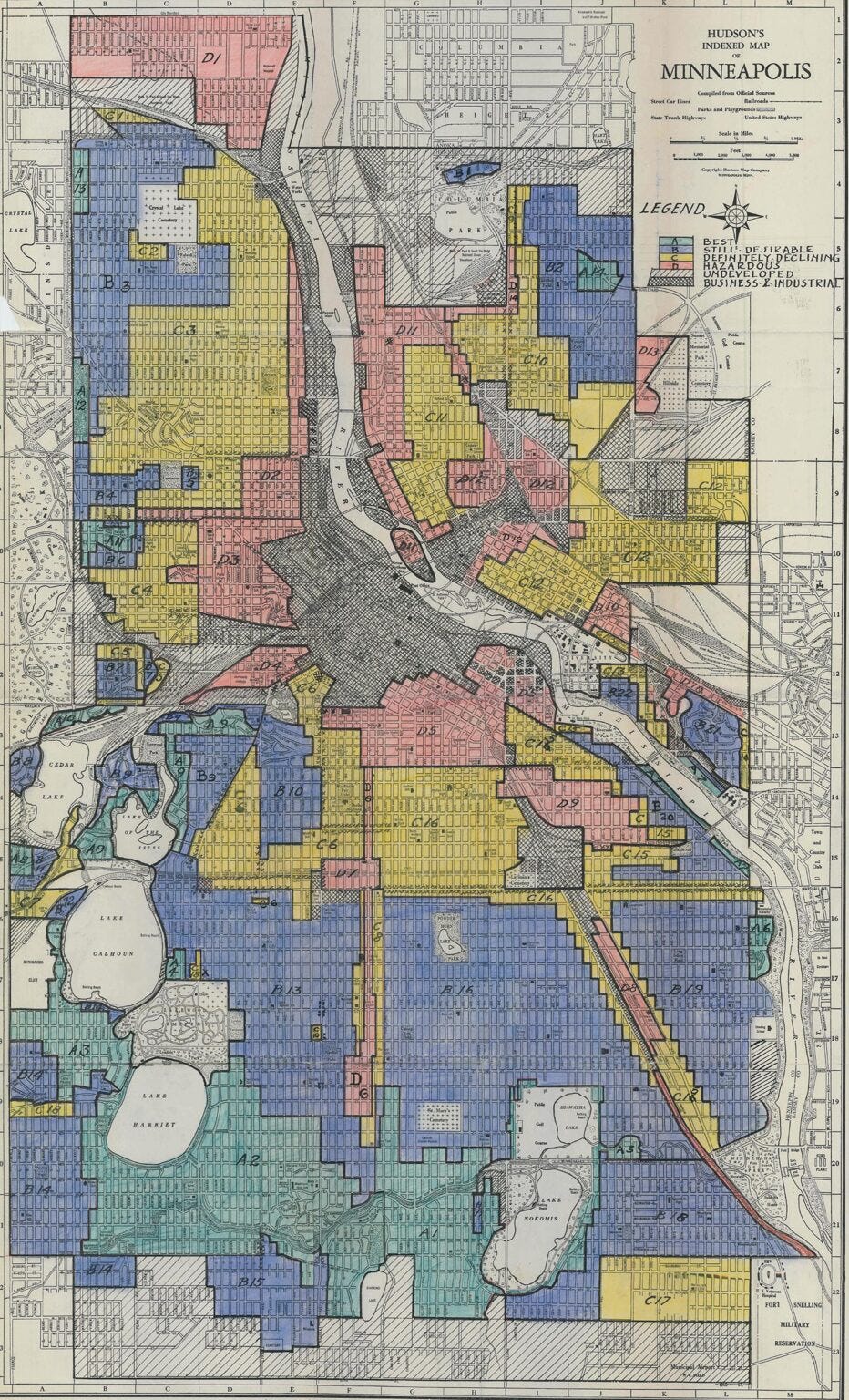

Minneapolis didn’t have overt Jim Crow laws, but it did have very strict implicit ones. Racially restrictive covenants started to appear in 1910 after several Black families moved into certain neighborhoods that some white people thought should be off limits to them. (Read about the Jacksons and Simpson families’ experiences in the Prospect Park neighborhood, and the Lee family’s attempt to cross the invisible yet real color line in South Minneapolis.) Minneapolis’ HOLC map concentrated Blacks to specific neighborhoods, while the homes around Minneapolis’ famous lakes and parkways were labeled green.

Just as in Tulsa, in Minneapolis and neighboring St. Paul, urban renewal projects demolished large parts of historic Black neighborhoods, with interstate highways creating barriers around majority Black neighborhoods. In Minneapolis, I-35W construction removed nearly 1,000 buildings and displaced between 24,000 - 30,000 people. St. Paul experienced a devastating loss of its own when I-94 ripped through the longstanding Rondo neighborhood.

Minneapolis and Tulsa were just two of over 400 cities where this happened. As historian Brent Cebul put it, “At the very moment when the civil rights movement secured voting rights and the desegregation of public and private spaces, the federal government unleashed a program that enabled local officials to simply clear out entire Black neighborhoods. Federal subsidies went to more than 400 cities, suburbs, and towns, supported more than 1,200 projects, and displaced a minimum of 300,000 families—perhaps some 1.2 million Americans. While Black Americans were just 13 percent of the total population in 1960, they comprised at least 55 percent of those displaced.”

Like residents of Tulsa who hadn’t learned of the race massacre that happened in their community until decades later, Minneapolitans are still just slowly learning about how Jim Crow-like social norms were being practiced right in our own city.

The Minneapolis Fire Department had a Black-only fire station from 1907-1941, because white firefighters refused to share living facilities with Black men. After it closed in 1941, there were no nonwhite firefighters for another 30 years. A lawsuit in the early 1970s forced Minneapolis to hire qualified non-white men. (The first woman firefighter was hired in 1986.)

Anthony Cassius, civil rights and labor leader in the hospitality business, was denied a liquor license and bank financing for several years because he was told that Blacks could only operate “barbecues, shoeshine parlors and barbershops.” In 1949 he became the first African American to open an integrated restaurant and club to receive a liquor license in Minneapolis. (I was amazed to learn that Cassius himself was a refugee from the Tulsa Race Massacre, arriving in Minneapolis from Tulsa in 1921 at the age of 13. Before opening up the Cassius Club Cafe in downtown Minneapolis, he owned the Dreamland Cafe in the historic Black neighborhood in South Minneapolis. I want to explore more about his possible connection to the famous Dreamland Theater in Tulsa.)

In 1939, nationally recognized Black singer Marian Anderson was denied a room at the lavish Dyckman Hotel during her visit to Minneapolis because of her race. During prior visits, Anderson stayed at the Phyllis Wheatley House, which was where many Black entertainers stayed when they were passing through town because they were not allowed to stay in “white” hotels. Protests from a coalition of civil rights groups forced the Dyckman management to reverse this decision and in the end, Anderson entered through the front door.

Just last week, the state’s major newspaper, the Minnesota Star Tribune, ran a front page story about one woman’s mission to document the history of the Ku Klux Klan in Minnesota: “People don’t want to believe that it happened here,” Nancy Vaillancourt said. “I want people to know the truth. I want them to know it did happen.”

And of course we can’t forget the international racial reckoning that was triggered by a Minneapolis police officer's killing of an unarmed, nonviolent Black man, George Floyd, on Memorial Day 2020.

I went to Tulsa looking for understanding about how a city could ever recover from such a destructive incident of racial violence. Surely, Tulsa’s uniquely horrific experience with the race massacre would have left it smothered in a feeling of shame that it is still trying to get over. Instead, I found that Tulsa’s experience taught me more about my own hometown. Both cities – indeed, most cities across the country that were built up in the early 1900s – have all been impacted by some level of racial violence, and the sordid combination of housing segregation laws, racially restrictive covenants, redlining, urban renewal, and highway construction. Liberal Minneapolis’ and Minnesota’s decisions about which neighborhoods to bulldoze for highways to connect downtowns to growing suburbs were no less racially prejudiced as conservative Tulsa’s and Oklahoma’s was. The geography of our cities and stubborn racial wealth gap are all contemporary consequences of those decisions.

Thanks for the mirror, Tulsa.

This is the seventh part of my series Blue City Warrior Visits Red America: In Search of Us. Go HERE to read the Blue City Warrior opening essay. Please subscribe to follow my journey!

Additional Resources

Brandy Colbert, 2021, Black Birds in the Sky, The story and legacy of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre

Tulsa Historical Society and Museum: 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre

Human Rights Watch, May 2020: The Case for Reparations in Tulsa, Oklahoma

Forbes, Antoine Gara, May 31, 2021, The Baron of Black Wall Street

Wall Street Journal, Keiko Morris, May 29, 2021, Black Land Ownership Primed Greenwood’s Rebound After Massacre

The Counselors of Real Estate (CRE), November 2020: America’s Sordid History of Exclusionary Zoning

Nonprofit Quarterly, Steve Dubb, July 27, 2022, What Really Destroyed Tulsa’s Black Wall Street

Next City, Carlos Moreno, May 31, 2021, Black Wall Street’s Second Destruction: After the Race Massacre, Greenwood rebuilt strong. Then came “urban renewal.”

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, February 25, 2021, Systemic racism haunts homeownership rates in Minnesota: How generations of discriminatory policies and practices created and reinforce racial disparities in homeownership

Very interesting and informative Cara!